The Singapore River is a river that flows parallel to Alexandra Road and feeds into the Marina Reservoir in the southern part of Singapore. Once a bustling trade centre, the river became heavily polluted due to rapid urbanisation and expanding trade activities. The absence of pollution control facilities allowed oil spills, sewage, solid waste, and industrial by-products to contaminate the water, leading to severe environmental degradation. In 1977, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew initiated a massive clean-up operation, aiming to transform the river and improve the quality of life for Singaporeans. The clean-up was successfully completed in 1987, and the river now boasts a dynamic combination of old and new, with a thriving leisure and entertainment scene.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of cleanup call | 27 February 1977 |

| Cleanup duration | 10 years |

| Cost of cleanup | $170 million |

| Number of relocated squatters | 4,000 |

| Number of relocated hawkers | 5,000 |

| Number of relocated vegetable sellers | 4,000 |

| Number of relocated bumboats | Hundreds |

| Number of relocated pig farms | 610 |

| Number of relocated duck farms | 500 |

| Number of relocated backyard trades and cottage industries | 2,800 |

| Date of completion | 2 September 1987 |

What You'll Learn

Garbage, sewage, and industrial waste

The Singapore River became a dumping ground for garbage, sewage, and industrial waste due to the absence of pollution control facilities. The river's pollution was caused by a variety of sources, including waste from pig and duck farms, unsewered premises, street hawkers, and vegetable wholesalers. Riverine activities such as transport, boat building, and repairs also contributed to the pollution, with oil spills and wastewater from boats and lighters.

The clean-up of the Singapore River involved the relocation of about 4,000 squatters and the provision of public housing for them. The government also addressed the issue of street hawkers and vegetable sellers, whose daily waste flowed into the river, by moving them to designated hawker centres. This relocation process impacted approximately 26,000 families, highlighting the scale of the issue.

The clean-up efforts also extended to addressing the pollution caused by pig and duck farms. A total of 610 pig farms and 500 duck farms were draining untreated waste into the waterways, and they were included in the relocation process. This was a significant step towards reducing the pollution levels in the river.

The clean-up operation also focused on removing sources of pollution, such as garbage, sewage, and industrial waste. The government implemented proper sewage infrastructure and took measures to minimise future pollution. The overall aim was to change people's way of life to ensure the river's cleanliness and promote sustainable development.

The Singapore River's transformation from a heavily polluted waterway to a clean and thriving leisure attraction is a testament to the country's commitment to sustainable development. The river's scenery now blends historic features with new developments, creating a dynamic environment for locals and tourists alike. The successful clean-up of the Singapore River sets a precedent for addressing environmental issues while pursuing economic growth.

Metro's Impact: Pollution or Progress?

You may want to see also

Oil spills from boats and lighters

The Singapore River has undergone a remarkable transformation, from a heavily polluted waterway to a thriving leisure destination. The river's clean-up, which took place between 1977 and 1987, addressed various sources of pollution, including oil spills and waste from boats and lighters.

The river's decline in economic importance made it easier for the government to initiate cleaning operations. The clean-up efforts, led by Lee Ek Tieng, involved various government departments and agencies. The relocation of lighters and other boats to upgraded facilities was a crucial aspect of the clean-up. The Port of Singapore Authority moved hundreds of bumboats and lighters to a new lighter anchorage at Pasir Panjang, away from the river.

The clean-up of the Singapore River and the relocation of boats and lighters were not without their challenges. The eviction of lighter operators and other river-dependent businesses disrupted livelihoods and impacted the river's cultural identity. However, the trade-off was the significant improvement in sanitation and safety, as well as positive ecological outcomes. The river's transformation has attracted wildlife, including species previously rare in Singapore, such as otters and monitor lizards.

The successful clean-up of the Singapore River is a testament to the country's commitment to sustainable development. By addressing the pollution caused by boats and lighters, the government improved the quality of life for its citizens and created a dynamic riverine scenery that blends the old and new.

Burning Things: A Major Cause of Pollution?

You may want to see also

Lack of pollution control facilities

The Singapore River was once a bustling hub of trade and commerce, but it came at a cost: severe pollution. The lack of pollution control facilities meant that oil, sullage water, and solid wastes were discharged into the river, exacerbating the already dire situation.

The absence of proper mechanisms to manage pollution allowed for the unchecked release of contaminants into the river. Oil spills from boats and lighters, for instance, contributed significantly to the problem. Without adequate facilities to contain and treat these spills, the oil slicked its way into the water, leaving a trail of destruction in its wake.

Solid waste, another major concern, was also a consequence of the lack of control facilities. The river became a dumping ground for garbage, sewage, and industrial waste. With no designated sites or systems in place to manage this waste, it ended up in the river, creating an eyesore and posing a significant health hazard.

The issue was further compounded by the discharge of sullage water, a type of wastewater, into the river. This water, often containing a mixture of sewage and industrial effluent, added to the river's pollution burden. Without facilities to treat this wastewater, it flowed freely into the river, degrading water quality and contributing to a foul stench.

The lack of pollution control facilities was a critical factor in the degradation of the Singapore River. It allowed for the unchecked release of oil, solid waste, and sullage water, which collectively inflicted severe environmental damage. This situation persisted until 1977 when the government, recognizing the urgency of the problem, initiated a comprehensive cleanup program, marking a turning point in the river's history.

How Pollution Influences Lightning Formation

You may want to see also

Pollution from pig and duck farms

The Singapore River has undergone a remarkable transformation from a heavily polluted waterway to a thriving leisure destination. The river's clean-up, which began in the 1970s, addressed various sources of pollution, including waste from pig and duck farms.

Pig and duck farms were significant contributors to the pollution of the Singapore River, particularly in the Kallang Basin area. In the early 1980s, Singapore faced the challenge of balancing limited resources with rapid development. As the demand for land increased, especially for housing, the environmental impact of pig farming became more apparent and challenging to ignore. The government recognised that pig farming was highly pollutive and resource-intensive, leading to a decision in 1984 to phase out this industry.

Pig farms were major sources of both land and water pollution. Their untreated waste was drained directly into the waterways, severely affecting water quality. This issue was exacerbated by the lack of pollution control facilities, allowing oil, sullage water, and solid wastes to be discharged into the river, further deteriorating its condition.

The clean-up of the Singapore River and Kallang Basin was a massive undertaking, costing the government a significant amount of money and requiring the relocation of thousands of people living and working in the area. The success of the river's clean-up is evident in the re-emergence of monitor lizards and otters, species rarely seen in Singapore previously.

The phasing out of pig farming in Singapore presented challenges and opportunities for local farmers. Some farmers, like Koh Swee Lai, chose to adapt by switching to alternative types of livestock or embracing new technologies in different sectors, such as egg farming. The government provided support during this transition, offering loans and investments to facilitate the exploration of new agricultural paths.

The clean-up of the Singapore River was not only about environmental restoration but also reflected a shift in the river's economic role. Once a bustling trade artery, the river's significance in trade diminished over time, making it easier for the government to initiate and pursue extensive cleaning operations.

Noise Pollution: Cardiovascular Health Risks and Hazards

You may want to see also

Unsanitary living conditions

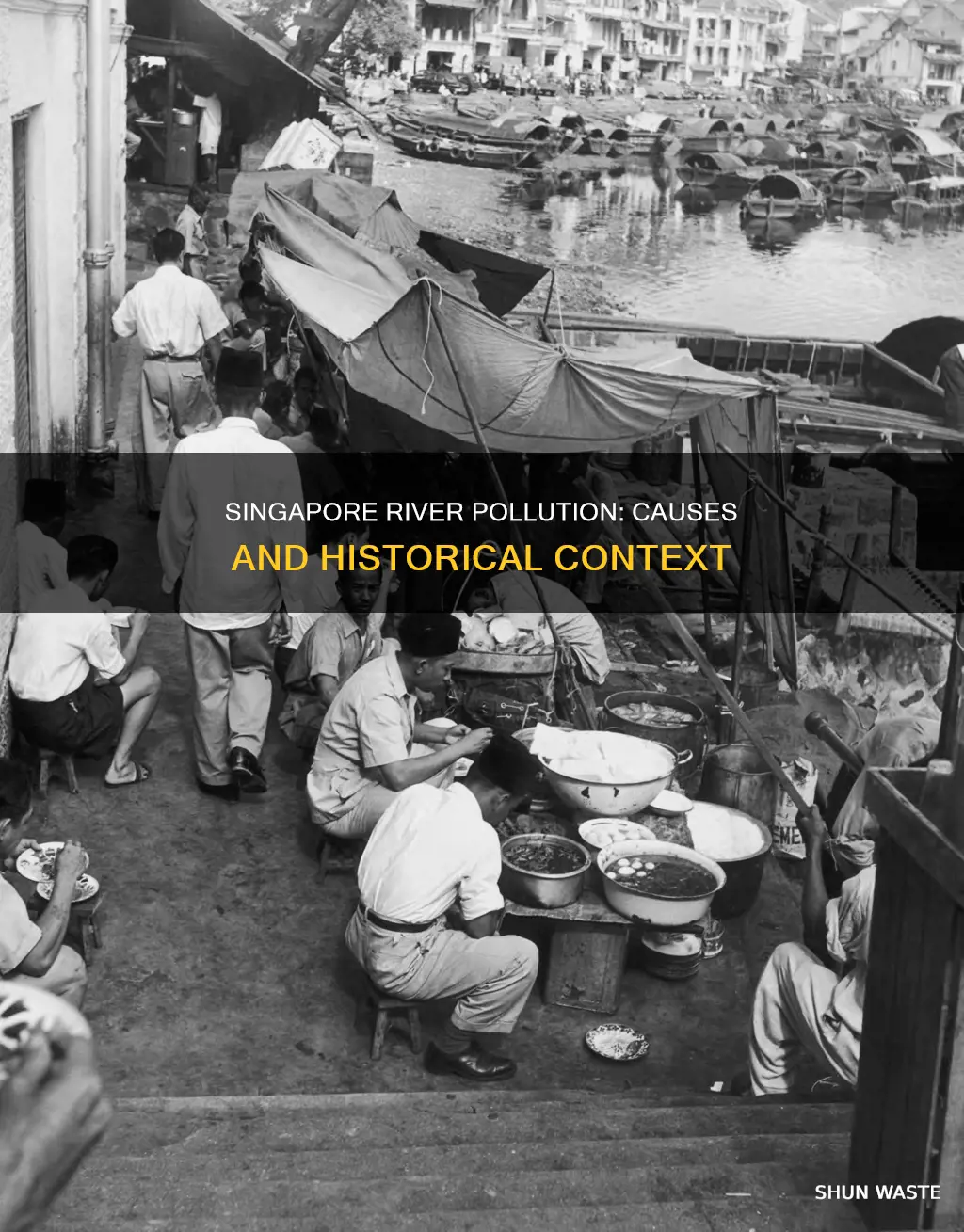

The Singapore River and the Kallang Basin were heavily polluted due to unsanitary living conditions. In the 1970s, the banks of the river were crowded with squatters, hawkers, and manufacturing industries. The river had become the centre of trade and commercial activities by the end of the 19th century. As businesses flourished and the number of people living and working along the river grew, the waterway became increasingly polluted.

The sources of water pollution in the Singapore River and Kallang Basin included waste from pig and duck farms, unsewered premises, street hawkers, and vegetable wholesalers. In 1977, it was reported that more than 40,000 squatters were living in unsanitary conditions in the vicinity of the rivers, and liquid and solid wastes from the hawkers, vegetable vendors, markets, and unsewered premises continued to represent a serious source of pollution. The river was also polluted by riverine activities such as transport, boat building, and repairs. Oil spills and wastewater from boats and lighters added to the pollution of the rivers.

The government eventually mounted a large-scale clean-up, which took place between 1977 and 1987. The clean-up involved the relocation of about 4,000 squatters, along with hawkers and vegetable sellers, whose daily waste flowed into the river. Public housing was provided for the squatters, while street hawkers were moved to purpose-built hawker centres. The clean-up also included the removal of foul-smelling mud from the banks and the bottom of the river, as well as the clearance of debris and other rubbish.

The Singapore River clean-up was a massive exercise that addressed the unsanitary living conditions and improved the sanitation and safety of the area. The relocation of residents and businesses, as well as the implementation of anti-pollution measures, were crucial aspects of the clean-up plan. The successful transformation of the Singapore River has set an example for the Republic's commitment to sustainable development.

Air Pollution: Understanding the Causes and Effects

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Singapore River became polluted due to the disposal of garbage, sewage, and industrial waste. The sources of water pollution included waste from pig and duck farms, unsewered premises, street hawkers, and vegetable wholesalers. Riverine activities such as transport, boat building, and repairs also contributed to the pollution.

The clean-up of the Singapore River began in 1977, with a speech by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew at the opening ceremony of the Upper Peirce Reservoir. The Master Plan for the cleaning of the Singapore River and Kallang Basin was drafted after 8 months of study.

The clean-up of the Singapore River took 10 years, from 1977 to 1987. During this time, over 46,000 squatters were relocated, and nearly 5,000 hawkers and vegetable sellers were moved to hawker centers. The clean-up also involved the removal of various sources of pollution, the provision of proper sewage infrastructure, and the implementation of anti-pollution measures.