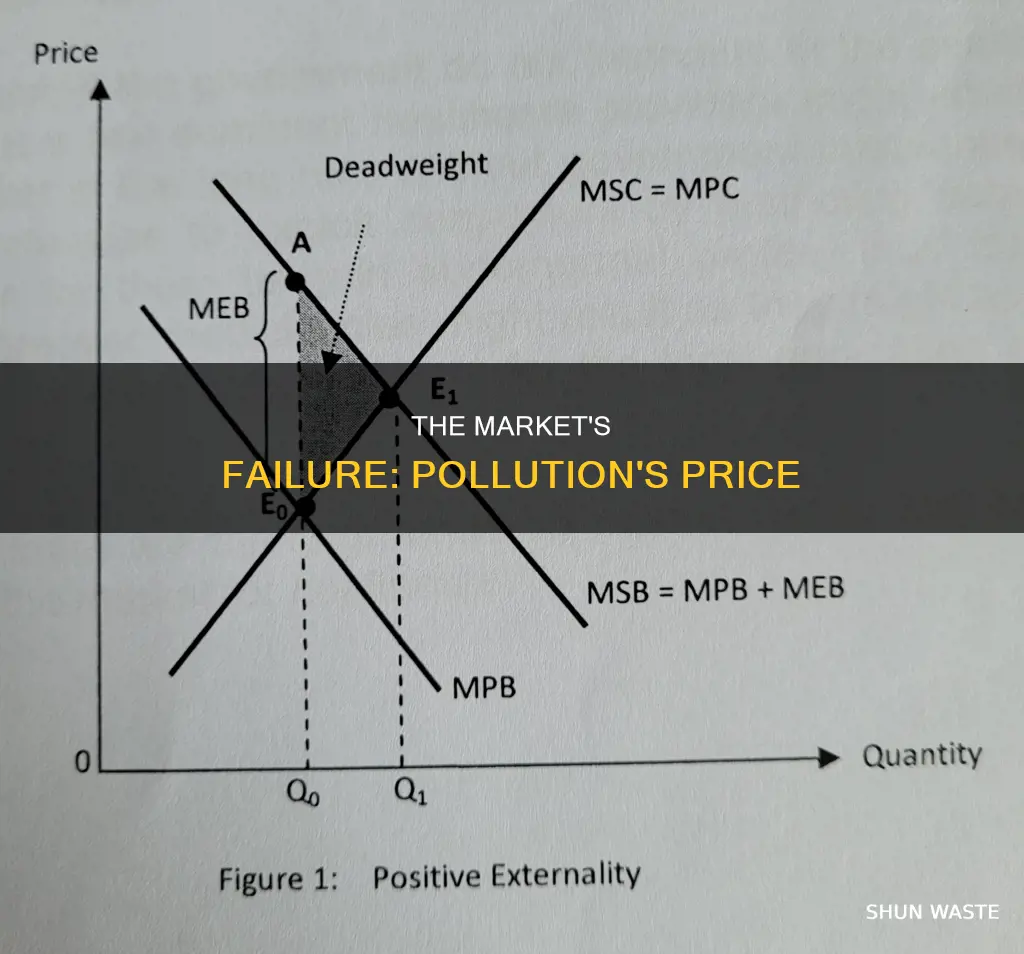

The price system is often unable to effectively address the pollution problem due to the presence of externalities. Market prices do not account for the costs and benefits associated with pollution, leading to market failures. This is further exacerbated by the long-term nature of environmental degradation and the tendency to discount future costs, resulting in the under-pricing of pollution. The immediate benefits of polluting, such as increased production or cheaper raw materials, often outweigh the long-term consequences, causing polluters to not fully internalise the impact of their actions. Regulatory failures can also undermine the mechanisms designed to address pollution, impacting public health, ecosystems, and environmental sustainability. To address these issues, various solutions have been proposed, including the implementation of a carbon tax to increase the cost of pollution and encourage the adoption of cleaner technologies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Market prices do not account for the costs and benefits associated with pollution | Market failure |

| The long-term nature of environmental degradation and the associated costs | Future costs are discounted |

| Information asymmetry | Firms have superior information about the environmental consequences of their activities |

| Regulatory failures | Measures that enhance transparency and accountability within government agencies are needed |

| Discounting of future costs associated with pollution | Carbon tax could increase the cost of pollution |

What You'll Learn

- The price system does not account for the costs and benefits associated with pollution, leading to market failures

- The long-term nature of environmental degradation and the associated costs are not adequately addressed by the price system due to the tendency to discount future costs

- Regulatory failures can undermine the very mechanisms designed to address pollution, which can have detrimental effects on public health, ecosystems, and the overall sustainability of the environment

- The discounting of future costs associated with pollution is a critical factor in why the price system may not effectively address environmental degradation

- Information asymmetry: firms have superior information about the environmental consequences of their activities, which they can exploit at the expense of the environment and society

The price system does not account for the costs and benefits associated with pollution, leading to market failures

The price system, while efficient in many economic contexts, often fails to adequately address pollution due to the long-term nature of environmental degradation and the associated costs. Market prices do not account for the costs and benefits associated with pollution, leading to market failures. This is due to the presence of externalities, such as information asymmetry, where firms have superior knowledge about the environmental consequences of their activities and exploit this to their advantage.

One significant issue is the tendency to discount future costs, which can lead to the under-pricing of pollution. The immediate benefits of polluting, such as increased production or cheaper raw materials, often outweigh the long-term consequences. As a result, polluters may not internalise the full impact of their actions, and future generations bear the brunt of pollution, including health issues, environmental degradation, and the costs of cleaning up.

Regulatory failures can also undermine the very mechanisms designed to address pollution, with detrimental effects on public health, ecosystems, and the overall sustainability of the environment. To address this, measures that enhance transparency and accountability within government agencies are crucial. This could include stricter lobbying regulations, increased public scrutiny, and the establishment of independent oversight committees.

To effectively address the pollution problem, it is essential to recognise and address externalities through appropriate policies, such as taxation or regulation. Policymakers and economists have proposed solutions such as a carbon tax, which would increase the cost of pollution by reflecting its true environmental impact, and 'natural capital accounting', which assigns a monetary value to natural resources and environmental services. By implementing such measures, societies can better manage and mitigate the negative impacts of pollution while promoting sustainable economic growth.

Ozone Pollution: Why It Can't Replace Stratospheric Ozone

You may want to see also

The long-term nature of environmental degradation and the associated costs are not adequately addressed by the price system due to the tendency to discount future costs

The price system often fails to adequately address pollution due to the long-term nature of environmental degradation and the associated costs. One significant issue is the tendency to discount future costs, which can lead to the under-pricing of pollution. This occurs because the immediate benefits of polluting, such as increased production or cheaper raw materials, often outweigh the long-term consequences. As a result, polluters may not internalise the full impact of their actions, leading to a market failure.

The price system's inability to address pollution effectively also stems from the presence of externalities. Market prices do not account for the costs and benefits associated with pollution, leading to market failures. By recognising and addressing these externalities through appropriate policies, such as taxation or regulation, societies can better manage and mitigate the negative impacts of pollution while promoting sustainable economic growth.

The discounting of future costs associated with pollution is a critical factor in why the price system may not effectively address environmental degradation. This phenomenon can be observed when the immediate benefits of polluting outweigh the long-term consequences, resulting in a failure to internalise the full impact of polluting activities.

To address this issue, policymakers and economists have proposed various solutions. One approach is to implement a carbon tax, which would increase the cost of pollution by reflecting the true environmental impact. This tax would encourage polluters to reduce emissions and invest in cleaner technologies, as they would be directly responsible for the costs associated with their pollution.

Air Pollution's Hidden Health Hazards

You may want to see also

Regulatory failures can undermine the very mechanisms designed to address pollution, which can have detrimental effects on public health, ecosystems, and the overall sustainability of the environment

The price system's inability to address pollution effectively stems from the presence of externalities. Market prices do not account for the costs and benefits associated with pollution, leading to market failures. Regulatory failures can occur when firms have superior information about the environmental consequences of their activities, allowing them to exploit this knowledge to their advantage, often at the expense of the environment and society. This information asymmetry can result in regulatory capture, where industry influence undermines the effectiveness of government agencies.

To address this issue, measures that enhance transparency and accountability within government agencies are crucial. This includes stricter lobbying regulations, increased public scrutiny, and the establishment of independent oversight committees. Additionally, fostering a culture of integrity and ethical decision-making within these agencies can help ensure their independence and focus on the public interest.

Furthermore, the long-term nature of environmental degradation and the associated costs pose significant challenges to the price system. The tendency to discount future costs can lead to the under-pricing of pollution, as the immediate benefits of polluting, such as increased production or cheaper raw materials, often outweigh the long-term consequences. As a result, polluters may not fully internalize the impact of their actions, shifting the burden of pollution to future generations, who bear the costs of health issues, environmental degradation, and cleanup efforts.

To address this issue, policymakers have proposed solutions such as implementing a carbon tax to increase the cost of pollution and reflect its true environmental impact. This would encourage polluters to reduce emissions and invest in cleaner technologies by holding them directly responsible for the costs associated with their pollution. Additionally, the concept of 'natural capital accounting' assigns a monetary value to natural resources and environmental services, ensuring their consideration in economic decision-making.

Understanding Soil Pollution: Testing Methods and Techniques

You may want to see also

The discounting of future costs associated with pollution is a critical factor in why the price system may not effectively address environmental degradation

The price system, while efficient in many economic contexts, often fails to adequately address pollution due to the long-term nature of environmental degradation and the associated costs. One significant issue is the tendency to discount future costs, which can lead to the under-pricing of pollution. This phenomenon occurs because the immediate benefits of polluting, such as increased production or cheaper raw materials, often outweigh the long-term consequences. As a result, polluters may not internalise the full impact of their actions, leading to a market failure. Future generations bear the brunt of pollution, including health issues, environmental degradation, and the costs of cleaning up and mitigating the effects of pollution.

To address this issue, policymakers and economists have proposed various solutions. One approach is to implement a carbon tax, which would increase the cost of pollution by reflecting the true environmental impact. This tax would encourage polluters to reduce emissions and invest in cleaner technologies, as they would be directly responsible for the costs associated with their pollution. Additionally, governments can employ the concept of 'natural capital accounting', which assigns a monetary value to natural resources and environmental services, ensuring that these factors are considered in economic decision-making.

Thermal Pollution Control: Strategies to Combat Rising Temperatures

You may want to see also

Information asymmetry: firms have superior information about the environmental consequences of their activities, which they can exploit at the expense of the environment and society

The price system, while efficient in many economic contexts, often fails to adequately address pollution due to the long-term nature of environmental degradation and the associated costs. One significant issue is the tendency to discount future costs, which can lead to the under-pricing of pollution. This phenomenon occurs because the immediate benefits of polluting, such as increased production or cheaper raw materials, often outweigh the long-term consequences. As a result, polluters may not internalise the full impact of their actions, leading to a market failure.

Information asymmetry plays a crucial role in understanding why the price system may fail to effectively address pollution issues. When firms have superior information about the environmental consequences of their activities, they can exploit this knowledge to their advantage, often at the expense of the environment and society. This can lead to regulatory failures, which can undermine the very mechanisms designed to address pollution.

To combat this issue, it is crucial to implement measures that enhance transparency and accountability within government agencies. This could include stricter lobbying regulations, increased public scrutiny, and the establishment of independent oversight committees. Additionally, fostering a culture of integrity and ethical decision-making within these agencies can help ensure that they remain independent and focused on the public interest, even in the face of industry influence.

By addressing regulatory capture and implementing solutions such as a carbon tax or 'natural capital accounting', policymakers and economists can improve the likelihood that price-based solutions will be effective in tackling pollution and promoting a healthier environment.

Heavy Metal Pollution: Prostate Cancer Trigger?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The price system fails to address pollution due to the presence of externalities. Market prices do not account for the costs and benefits associated with pollution, leading to market failures.

The long-term consequences of pollution include health issues, environmental degradation, and the costs of cleaning up and mitigating the effects of pollution. Future generations will bear the brunt of these consequences.

The discounting of future costs can lead to the under-pricing of pollution. The immediate benefits of polluting, such as increased production or cheaper raw materials, often outweigh the long-term consequences, resulting in market failure.

To improve the effectiveness of the price system, it is crucial to address regulatory capture and implement measures that enhance transparency and accountability within government agencies. This could include stricter lobbying regulations, increased public scrutiny, and the establishment of independent oversight committees. Additionally, policymakers and economists have proposed solutions such as implementing a carbon tax and employing the concept of 'natural capital accounting' to reflect the true environmental impact of pollution.