Brazil has been facing issues with air pollution, oil pollution, and deforestation. Air pollution, caused by vehicles, construction equipment, and more, can have detrimental effects on human health and the planet. Oil pollution, often a result of marine traffic and small spills, can harm the environment and human health. Deforestation in Brazil, driven by economic incentives and extractive growth models, has led to significant financial losses, social setbacks, and biodiversity loss. To address these issues, Brazil needs to implement solutions such as reducing air pollution through electric vehicles and public transportation, preventing oil spills through proper maintenance, and enforcing laws to protect forests and promote sustainable land use.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Solutions to air pollution | Reducing energy production from burning coal, developing a personalized Brazilian version of an air quality index, alerting the population to the increased risk of pollutants |

| Solutions to oil pollution | Scrutinizing the consequences of air pollution from oil, denying proposals to explore deep water wells in the Foz do Amazonas Basin, negotiating to use satellites from India to improve monitoring of deforestation |

| Solutions to deforestation | Reducing deforestation and implementing the Forest Code, improving agricultural and ranching practices, restoring forests, shutting down illegal sawmills, seizing illegal timber and vehicles, reforestation |

What You'll Learn

- Brazil's National Oil Spill Contingency Plan outlines response strategies for oil spills

- Brazil's air pollution issues are linked to urbanisation and slums

- Brazil has reduced Amazon deforestation by expanding its network of indigenous reserves

- Brazil's agricultural growth has come at the expense of native ecosystems

- Public policies and markets are needed to slow deforestation

Brazil's National Oil Spill Contingency Plan outlines response strategies for oil spills

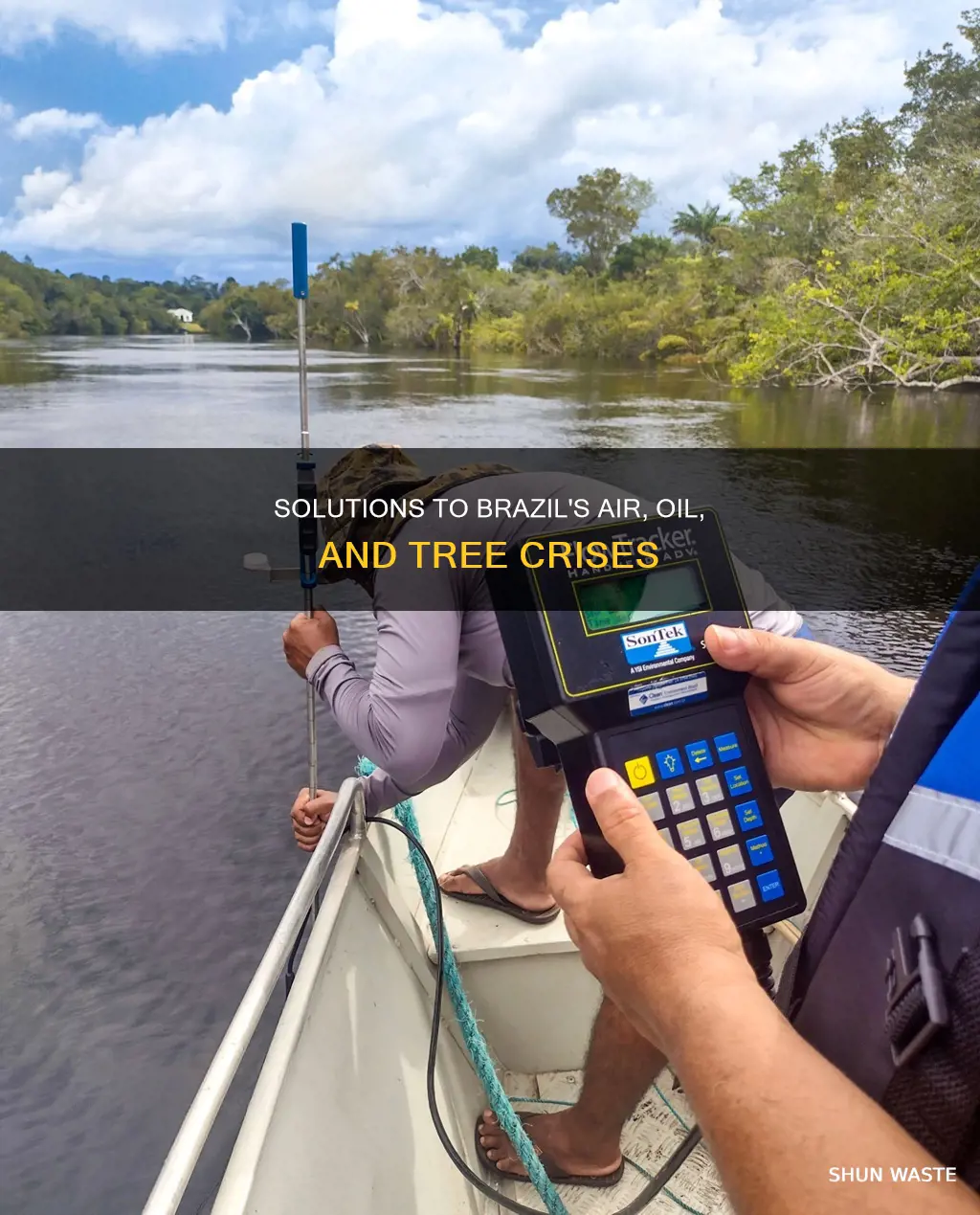

Brazil's National Oil Spill Contingency Plan, enacted in October 2013, outlines response strategies for oil spills in the country. The plan is designed to address the environmental and economic impacts of oil spills and includes measures to enhance response efficiency and mitigate ecological and economic damage.

The National Oil Spill Contingency Plan designates a coordinating authority and operational contact point for effective communication and coordinated operations during spills. In Brazil, the Marine Rescue Coordination Center (MRCC) serves as the operational contact point for receiving, transmitting, and processing urgent reports on incidents involving harmful substances, including oil spills from ships. The individual ports act as alternative contact points.

In the event of an oil spill, the Brazilian environmental agency, IBAMA, typically devolves the clean-up response to the environment departments of the 18 coastal states and/or to the national oil company, Petrobras. Petrobras has established nine Oil Spill Response Centres (CDA – Centro de Defesa Ambiental) at strategic locations throughout Brazil to facilitate the response process.

According to information from IBAMA in 2008, mechanical containment and recovery are the primary lines of defence against oil spills in Brazil, with mechanical dispersion as a supplementary measure. Training courses are conducted for Petrobras staff, port authorities, civil defence agencies, NGOs, and other interested parties to ensure effective preparedness and response.

The National Oil Spill Contingency Plan aligns with Brazil's commitments under international treaties, such as the 1990 International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Cooperation. This convention emphasizes the importance of contingency plans and international cooperation in addressing oil spills and accidents.

Scrubbers: Effective Air Pollution Solution?

You may want to see also

Brazil's air pollution issues are linked to urbanisation and slums

Brazil's air pollution issues are closely tied to the country's rapid urbanisation and the growth of slums. The nation's cities, particularly those with significant industrial activity, have recorded some of the country's highest mortality rates linked to air pollution. The state of São Paulo has been affected by black smoke from forest fires, a major source of carbon emissions, and industrial smoke from an ethanol plant in the metropolitan area of Ribeirão Preto.

The metropolitan area of São Paulo (MASP) has been a significant contributor to air pollution, with its emissions accounting for up to 80% of the O3 concentration in communities over 200 km away. The city of São Caetano do Sul, located in the ABC Paulista industrial region, recorded 320 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants between 2021 and 2023 directly attributable to air pollution. Other cities with notably high rates include Osasco, Guarulhos, and the capital, São Paulo, which are among the most polluted cities in Brazil.

The growth of slums, a consequence of rapid urbanisation, has also been linked to worsening air quality. Slums are often characterised by high population density, inadequate infrastructure, and limited access to basic services, including waste management. Brazil already faces significant challenges in waste management, with less than 60% of collected waste being adequately disposed of, according to Alfaia et al. (2017). Inadequate waste management practices can lead to open burning of waste, releasing toxic pollutants into the air and exacerbating air quality issues.

Additionally, Brazil's air pollution problems extend beyond its urban centres. The production and use of biofuels, such as ethanol, have been shown to impact air quality in rural areas. While government policies have helped reduce primary pollutant emissions in cities, secondary pollutants like surface ozone (O3) have increased. O3 concentrations in rural areas are influenced by ethanol production activities, and the impact can be felt in communities far from the production sites.

The country's air pollution issues are further compounded by deforestation, particularly in the Amazon region. Since 1985, more than half a million square kilometres of the Amazon rainforest have been lost due to deforestation. This deforestation often leads to fires, which produce air pollution that poses severe health risks to nearby communities. The burning of vegetation and forest residues releases a mixture of toxic pollutants that can linger in the air for weeks, affecting both local and distant areas.

Air Pollutants: Human-Caused Impacts on Our Atmosphere

You may want to see also

Brazil has reduced Amazon deforestation by expanding its network of indigenous reserves

Brazil is home to Earth's largest tropical rainforest, the Amazon, which covers nearly half of Brazil's territory and nine of its states. The Amazon is an essential and irreplaceable ecosystem, housing the most biodiverse forest in the world, the largest freshwater reservoir, and the most critical climate-regulating forest block on the planet.

The Amazon region's economy and Brazil as a whole rely heavily on farming, mining, and other resource-intensive activities that deplete the Amazon. Deforestation in the Amazon began in the 1960s and has accelerated in recent years, reaching a fifteen-year high in 2021. This deforestation has severe consequences for the environment and public health. When trees are cut down, carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change. Deforestation also leads to fires, which produce air pollution that poses a severe health risk, particularly to children, older people, pregnant people, and those with pre-existing health conditions.

Indigenous peoples are the primary protectors of the Amazon forests, and their lands play a crucial role in reducing deforestation. Studies have shown that collective property rights in Indigenous territories reduce deforestation in the Amazon. Additionally, Indigenous peoples possess traditional knowledge about food and pharmaceutical resources, contributing to the region's bioeconomy and providing economic benefits.

Recognizing the importance of Indigenous lands, Brazil has expanded its network of indigenous reserves, which has contributed to reducing deforestation. Between 2001 and 2018, Indigenous territories and protected areas in the Brazilian Legal Amazon (BLA) expanded, resulting in a marked reduction in deforestation, although some gains have been eroded in recent years.

While Brazil has made progress in reducing Amazon deforestation, the country continues to face challenges. There has been a lack of strong governmental commitment to environmental issues, with President Bolsonaro weakening environmental protections and pushing to open Indigenous lands to commercial exploitation. However, with the return of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to power in 2023, there is renewed hope for socioeconomic change and environmental protection.

Air Purification Towers: Pollution Solution or Futile Effort?

You may want to see also

Brazil's agricultural growth has come at the expense of native ecosystems

Brazil has become an agricultural powerhouse, producing roughly 30% of the world's soy and 15% of its beef by 2013. However, this agricultural growth has historically come at the expense of native ecosystems, particularly the Amazon rainforest and the Cerrado. Since 1985, pastures and croplands have replaced nearly 65 million hectares of forests and savannas in the legal Amazon. This large-scale conversion of ecosystems into agricultural land has resulted in the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change.

The Amazon region, which covers nearly half of Brazil's territory and includes nine of its states, has been a particular focus of deforestation. More than half a million square kilometres of the Amazon have been razed since 1985. This deforestation is driven by the cattle, forestry, and agribusiness industries, which clear land for cattle grazing, agriculture, and land speculation. The remaining vegetation is often set ablaze, resulting in fires that produce air pollution and pose severe health risks to vulnerable groups such as children, older people, pregnant people, and those with pre-existing health conditions.

The expansion of agriculture over ecosystems has led to negative social and environmental outcomes. It has been associated with rural violence, poverty, and pollution. Additionally, the Brazilian government has been criticised for its lack of commitment to environmental issues, with President Lula facing criticism for his weak opposition to congressional moves that diluted the powers of environmental ministries.

However, there are efforts underway to reconcile agricultural growth with environmental protection in Brazil. The Conservancy is working with the government, farmers, and corporations to reduce and stop deforestation. They are promoting better monitoring of deforestation, implementing the Forest Code, improving agricultural and ranching practices, and restoring forests on previously deforested land. Additionally, strategies such as eliminating land grabbing and land speculation, implementing payments for environmental services, and fostering sustainable intensification can help reduce deforestation while increasing production and social wellbeing.

While there are reasons to be cautiously optimistic about the future, with recent declines in Amazon deforestation rates and increased economic development through agriculture in southeast Brazil, it is crucial to continue addressing the negative impacts of agricultural growth on native ecosystems in Brazil.

Air Pollution: Unborn Health and Teratogen Risks

You may want to see also

Public policies and markets are needed to slow deforestation

Brazil has been identified as a key player in global climate change, with one of the world's largest emerging economies, a powerhouse of biodiversity, and the potential for renewable energy sources. Paradoxically, it is also a major polluter due to forest fires, deforestation, livestock, and the use of fossil fuels.

Deforestation has been Brazil's foremost cause of environmental and ecological degradation. Since 1970, over 600,000 square kilometres of Amazonian rainforest have been destroyed, and the rate of deforestation in protected zones increased by over 127% between 2000 and 2010. The Amazon region, home to over 20 million Brazilians, has seen more than half a million square kilometres razed since 1985. This has resulted in biodiversity loss, the release of stored carbon, and air pollution, with severe health risks for vulnerable groups.

Brazil's National Institute for Space Research (INPE) has helped reduce deforestation levels through its Real Time Deforestation Detection System (DETER) and the Amazon Deforestation Satellite Monitoring Project (PRODES). The government has also negotiated the use of satellites from India to improve monitoring. However, the abandonment of deforestation control policies and the encouragement of predatory agricultural practices will hinder progress.

The Conservancy is working with the government to better monitor deforestation and implement the Forest Code, as well as with farmers to improve practices and restore forests. By 2017, it was projected that this work would protect 24 million hectares against illegal deforestation, avoiding deforestation on 390,000 hectares and reducing carbon emissions by 290 million tons.

To effectively combat deforestation, Brazil needs to advance public policies related to environmental health, increase regulation, and address the complex characteristics of the urban-rural-industrial axis, where highly polluting activities often go unpunished.

US Cities With the Worst Air Pollution Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Brazil has made significant progress in reducing deforestation in the Amazon, which has lowered heat-trapping emissions more than any other country. However, the country's environmental policies have been criticised for their lack of attention to air pollution from the oil, gas, and coal industries. There is a growing need for scrutiny of the consequences of air pollution from these industries, especially on communities living near their facilities.

Brazil has expanded its network of indigenous reserves and protected areas, with indigenous peoples now controlling 20% of the Brazilian Amazon. The country has also strengthened its logging laws, with strict enforcement including seizures of illegal timber and the jailing of perpetrators. Additionally, Brazil has implemented social programs such as Fome Zero and Bolsa Familia, which have helped reduce hunger and poverty while increasing agricultural production.

Brazil has a National Oil Spill Contingency Plan that establishes a cooperative framework to reduce response times for incidents with significant environmental impacts. Mechanical containment and recovery are the primary defence against oil spills, with mechanical dispersion as a supplement. Petrobras, the national oil company, has established Oil Spill Response Centres at strategic locations throughout the country.

Cattle ranching is the primary driver of forest destruction in the Brazilian Amazon. Other factors include the economic incentive to clear land for agriculture and weak enforcement of forestry laws.

Deforestation is responsible for about 10% of global warming pollution. The Amazon rainforest stores large amounts of carbon, helping to stave off rapid climate change. When forests are cleared, this stored carbon is released into the atmosphere, contributing to heat-trapping emissions and global warming.