Lotic ecosystems are those with flowing water, such as rivers, streams, and springbrooks. They are defined by their unidirectional flow of water and are contrasted with lentic ecosystems, which involve relatively still terrestrial waters such as lakes, ponds, and wetlands. Lotic ecosystems are part of larger watershed networks or catchments, where smaller headwater streams drain into mid-size streams, which progressively drain into larger river networks.

Lotic ecosystems have two main zones: rapids and pools. Rapids are areas where the water is fast enough to keep the bottom clear of materials, while pools are deeper areas of water where the currents are slower and silt builds up. The major zones in lotic ecosystems are determined by the river bed's gradient or by the velocity of the current. Faster-moving turbulent water typically contains greater concentrations of dissolved oxygen, which supports greater biodiversity than the slow-moving water of pools.

Lotic ecosystems are often viewed and studied within the context of the River Continuum Concept, which conceptualises them as continuous entities with ever-changing physical and chemical variables that result in predictable physicochemical attributes and subsequent biological communities along this gradient. This perception is somewhat scale-dependent and is applicable at large scales; however, at smaller scales, physicochemical and biological patterns may seem random.

Lotic ecosystems are extremely fragile and provide important habitats for native fish, birds, aquatic organisms, and other riparian-dependent wildlife species. They are, however, susceptible to various threats, including drying, sedimentation, non-native species, and pollution.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type | Lotic ecosystems are flowing waters that can be perennial, intermittent, or ephemeral. |

| Lentic ecosystems are still water ecosystems. | |

| Examples | Lotic ecosystems include rivers, streams, springbrooks, and creeks. |

| Lentic ecosystems include ditches, seeps, ponds, seasonal pools, basin marshes, and lakes. | |

| Water flow | Lotic ecosystems have unidirectional water flow. |

| Lentic ecosystems have still water flow. | |

| Water depth | Lotic ecosystems have shallow waters. |

| Lentic ecosystems have deeper waters. | |

| Zones | Lotic ecosystems have two main zones: rapids and pools. |

| N/A | |

| Water composition | Lotic ecosystems must have atmospheric gases, turbidity, longitudinal temperature gradation, and dissolved materials. |

| N/A |

What You'll Learn

The impact of pollution on the food web in lotic ecosystems

Lotic ecosystems, or those with flowing water, are distinct from lentic ecosystems, which involve relatively still terrestrial waters such as lakes, ponds, and wetlands. Lotic waters can range from springs only a few centimetres wide to major rivers spanning kilometres in width. The unidirectional flow of water is the key factor influencing the ecology of lotic systems.

Lotic ecosystems are integral parts of larger watershed networks or catchments, where smaller headwater streams drain into mid-size streams, which then drain into larger river networks. The food base of streams within riparian forests is mostly derived from the trees, while wider streams and those without a canopy derive their food base from algae. Anadromous fish are also an important source of nutrients.

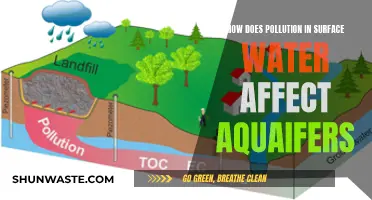

Lotic ecosystems are highly susceptible to environmental threats such as water loss, dams, chemical pollution, and introduced species. Pollution, in particular, can have detrimental effects on lotic food webs. For instance, elevated nutrient concentrations, especially nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilisers, can increase periphyton growth, which can be dangerous in slow-moving streams. Acid rain, formed from sulphur dioxide and nitrous oxide emitted by factories and power stations, can also lower the pH of lotic sites, affecting all trophic levels.

Moreover, pollution can disrupt the delicate balance of predator-prey interactions within the food web. It can lead to the decline or extinction of certain species, causing trophic cascades and affecting the abundance and distribution of other organisms in the ecosystem. Pollution can also introduce toxic substances that bioaccumulate in organisms, affecting their health and reproductive success.

In addition, pollution can have indirect effects on the food web by modifying the physical and chemical characteristics of the lotic ecosystem. For instance, pollution can alter water temperature, oxygen levels, and nutrient availability, which can, in turn, impact the growth and survival of primary producers and consumers.

Overall, pollution in lotic ecosystems can have far-reaching consequences on the food web, affecting species composition, biodiversity, and ecosystem functioning. The specific effects will depend on the type and extent of pollution, as well as the resilience and adaptability of the organisms within the ecosystem.

Noise, Light Pollution: Impact on Our Hydrosphere

You may want to see also

The effects of pollution on the biota in lotic ecosystems

Lotic ecosystems are flowing water systems that can be intermittent, perennial, or ephemeral. They include the associated riparian corridors and connecting ephemeral channels. These systems are extremely fragile and provide important habitats for native fish, birds, aquatic organisms, and other riparian-dependent wildlife species. The unidirectional flow of water is the key factor influencing their ecology.

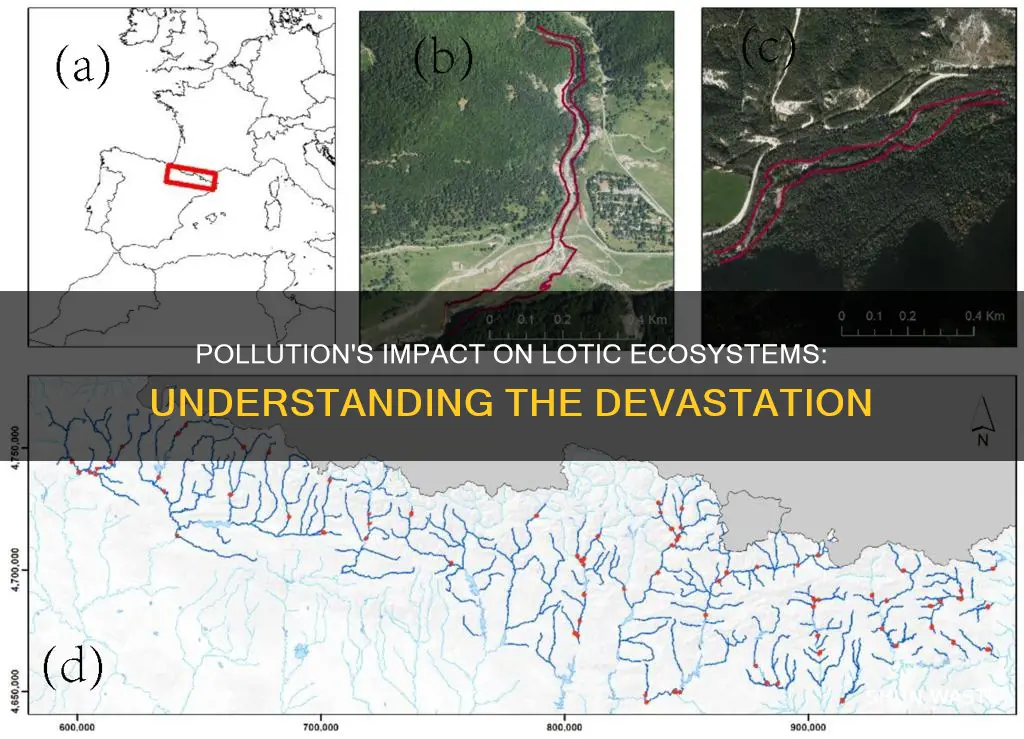

Lotic ecosystems are arranged in a network of various configurations and structures and can be studied from small spatial grains and extents to large macrosystem scales. They can be classified based on 'size' as represented by stream order. The processes at any site along the system are influenced by upstream processes and those in the watershed.

The riverine macrosystems are complex hierarchical systems nested spatially and temporally within continents, biomes, ecoregions, and basins. The main channels of rivers can be viewed as a network with different patterns of network shape, drainage density, network geometry, and longitudinal position and relative sizes of intersecting streams.

The river continuum concept (RCC) was an attempt to construct a single framework to describe the function of temperate lotic ecosystems from headwaters to larger rivers and relate key characteristics to changes in the biotic community. The RCC predicts a clinal response of organisms and ecological processes to gradual and continuous changes in physical conditions along a longitudinal dimension.

The RCC was later broadened to accommodate regional differences in hydrology, climate, tributaries, location-specific geology and lithology, vegetation, and human-induced factors to encompass broader spatial and temporal scales. More recent attempts to understand lotic ecology and benthic animal distributions at large scales include the Serial Discontinuity Concept (SDC), the Flood Pulse Concept (FPC), the Stream Biome Gradient Concept (SBC), and the Natural Flow Regime Concept (NFC).

The biota of lotic ecosystems is influenced by both hydrologic and hydraulic processes and forces. The former includes current velocities and discharge patterns, such as those related to flow and flood pulses. In contrast, the latter includes forces that have a direct physical impact on invertebrates or that affect them indirectly by altering substrate characteristics.

The riverine ecosystem synthesis (RES) describes the lotic ecosystems as structured by large hydrogeomorphic patches rather than gradual clines and incorporates conclusions of the natural flow regime model (NFR). The RES predicts that the nature of a downstream assemblage is inextricably linked with processes occurring upstream.

The biota of lotic ecosystems is also influenced by the chemical and thermal milieu. The distribution and abundance of freshwater invertebrates are correlated with the annual mean and range of temperatures and small-scale effects from groundwater inflows and degrees of shading. Certain natural chemical features of streams and lakes significantly affect invertebrate abundance and diversity by influencing habitat quality. Of these, the most crucial are probably dissolved oxygen and salinity (water hardness).

Human activities have a profound impact on lotic ecosystems and have altered their structure and function. These impacts include sewage effluent and fecal waste from human/animal activities, channelization for navigation purposes, removal of woody debris, straightening of channels, dam and reservoir construction, and more.

Air Pollution's Impact: Your Community's Health at Risk

You may want to see also

The sources of pollution in lotic ecosystems

- Agricultural fields: These fields often deliver large amounts of sediments, nutrients, and chemicals to nearby streams and rivers.

- Urban and residential areas: Contaminants from impervious surfaces such as roads and parking lots can also contribute to pollution when they drain into the ecosystem.

- Elevated nutrient concentrations: Especially nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizers, can increase periphyton growth, which can be dangerous in slow-moving streams.

- Acid rain: This forms from sulfur dioxide and nitrous oxide emitted from factories and power stations, dissolving in atmospheric moisture and entering lotic systems through precipitation, lowering the pH and affecting all trophic levels.

- Flow modification: Dams, water regulation, channel modification, and destruction of the river floodplain and adjacent riparian zones can all alter flow, temperature, and sediment regimes, impacting the ecosystem.

- Invasive species: These can be introduced through purposeful or unintentional events and can affect natives through competition, predation, habitat alteration, or the introduction of diseases and parasites.

Air Pollution's Impact on Our Circulatory System

You may want to see also

The impact of pollution on the abiotic components of lotic ecosystems

Abiotic factors are the non-living elements of an ecosystem that influence the way organisms function. The abiotic factors of lotic ecosystems include:

- Flow: The strength of water flow can vary between these systems, involving a continuum from torrential rapids to slow, backwaters that almost seem like lentic systems. The speed of the water flow can be variable within and across systems. It is typically based upon variability of friction with the bottom or sides of the channel, sinuosity, obstructions, and the incline gradient. Flowing waters can alter the shape of the streambed through processes of erosion and deposition, creating a variety of habitats, including riffles, glides, and pools.

- Light: Light is important to lotic systems, as it provides the energy necessary to drive primary production via photosynthesis, and can also provide refuge for prey species in shadows it casts. The amount of light that a system receives can be related to a combination of internal and external stream variables. Seasonal and diurnal factors might also play a role in light availability.

- Temperature: Most lotic species are poikilotherms, meaning their internal temperature varies with their environment. Water can be heated or cooled through radiation at the surface and conduction to or from the air and surrounding substrate. Shallow streams are typically well mixed and maintain a relatively uniform temperature within an area. In deeper, slower moving water systems, however, a strong difference between the bottom and surface temperatures may develop. Spring-fed systems have little variation as springs are typically from groundwater sources, which are often very close to ambient temperature. Many systems show strong diurnal fluctuations and seasonal variations are most extreme in arctic, desert and temperate systems. The amount of shading, climate and elevation can also influence the temperature of lotic systems.

- Water Chemistry: Water chemistry between systems varies tremendously. The chemistry is foremost determined by inputs from the geology of its watershed, or catchment area, but can also be influenced by precipitation and the addition of pollutants from human sources. Large differences in chemistry do not usually exist within small lotic systems due to a high rate of mixing. In larger river systems, however, the concentrations of most nutrients, dissolved salts, and pH decrease as distance increases from the river’s source.

- Oxygen: Oxygen is likely the most important chemical constituent of lotic systems, as all aerobic organisms require it for survival. It enters the water mostly via diffusion at the water-air interface. Oxygen’s solubility in water decreases as water temperature increases. Fast, turbulent streams expose more of the water’s surface area to the air and tend to have low temperatures and thus more oxygen than slow, backwaters. Oxygen is a byproduct of photosynthesis, so systems with a high abundance of aquatic algae and plants may also have high concentrations of oxygen during the day. These levels can decrease significantly during the night when primary producers switch to respiration. Oxygen can be limiting if circulation between the surface and deeper layers is poor, if the activity of lotic animals is very high, or if there is a large amount of organic decay occurring.

- Inorganic Substrate: The inorganic substrate of lotic systems is composed of the geologic material present in the catchment that is eroded, transported, sorted, and deposited by the current. Inorganic substrates are classified by size on the Wentworth scale, which ranges from boulders, to pebbles, to gravel, to sand, and to silt. Typically, particle size decreases downstream with larger boulders and stones in more mountainous areas and sandy bottoms in lowland rivers. This is because the higher gradients of mountain streams facilitate a faster flow, moving smaller substrate materials further downstream for deposition. Substrate can also be organic and may include fine particles, autumn shed leaves, submerged wood, moss, and more evolved plants. Substrate deposition is not necessarily a permanent event, as it can be subject to large modifications during flooding events.

Plastic Pollution's Impact on Italy's Environment and Ecology

You may want to see also

The impact of pollution on the lentic-lotic dichotomy

Lotic and lentic are two classifications of water bodies within the hydrological cycle. Lotic waters refer to flowing water bodies like rivers, streams, and brooks, while lentic waters refer to standing water bodies like lakes, ponds, and marshes.

Pollution affects lotic and lentic ecosystems differently due to their distinct hydrodynamic conditions. Lentic systems, with their longer residence times, may experience more pronounced effects of nutrient loading and temperature increases, leading to issues like eutrophication and algal blooms. On the other hand, lotic systems may be more susceptible to changes in flow regimes and sediment transport, impacting habitat availability and species composition.

Impact of pollution on lotic ecosystems

Pollution in lotic ecosystems can include increasing sediment export, excess nutrients from fertilisers, sewage and septic inputs, plastic pollution, nanoparticles, pharmaceuticals, and inorganic contaminants. These pollutants can reduce ecosystem functioning, limit ecosystem services, reduce biodiversity, and impact human health.

Lotic ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to the effects of pollution due to their dynamic and interconnected nature. Pollution can disrupt the continuous water movement in these ecosystems, altering the oxygen levels, nutrient transport, and biodiversity.

Impact of pollution on lentic ecosystems

Lentic ecosystems, with their standing water nature, may experience more prolonged exposure to pollutants. The still waters can act as reservoirs, accumulating pollutants over time. This can lead to increased nutrient loading, algal blooms, and reduced water quality.

Additionally, lentic ecosystems are often characterised by stratification, with temperature and oxygen gradients. Pollution can disrupt this stratification, affecting nutrient distribution and biological activity.

Management and conservation strategies

Conserving and restoring lotic and lentic ecosystems is crucial for maintaining their ecological functions and services. This includes protecting critical habitats, reducing pollution inputs, and enhancing connectivity between water bodies. Integrated management approaches that consider the interactions between lentic and lotic waters are essential for effective water management and conservation.

Pollution's Impact: Cities' Future at Stake

You may want to see also