When it comes to the impact of taxes on pollution, it's essential to understand the dynamics of demand and supply curves. Taxes on pollution are often implemented to address environmental concerns, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions and tackling climate change. By imposing taxes on pollution-causing goods or activities, governments aim to influence consumer behaviour and incentivize the adoption of more environmentally friendly alternatives. The impact of these taxes on the demand curve depends on whether the tax is levied on the producers or the consumers. When a tax is imposed on producers, the supply curve shifts upward, leading to a new equilibrium with higher prices and reduced quantity demanded. On the other hand, when the tax is levied on consumers, the demand curve shifts downward, indicating a decrease in the willingness to purchase the taxed goods or services at higher prices. Ultimately, the goal of pollution taxes is to create a market incentive for reducing pollution, either by discouraging the consumption of polluting goods or by encouraging the development and adoption of cleaner technologies and practices.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Effect on demand curve | A tax levied on consumers will shift the demand curve downwards |

| Effect on supply curve | A tax levied on producers will shift the supply curve upwards |

| Effect on consumer behaviour | Consumers will respond to the price increase by buying less |

| Effect on producer behaviour | Producers will pass some of the costs on as an increased price |

| Effect on government revenue | Depends on the tax rate and quantity of the product demanded |

| Effect on market equilibrium | A new equilibrium is created at a higher price and lower quantity |

What You'll Learn

Taxes on pollution can reduce inequality and raise revenue

Taxes on pollution can be an effective tool to reduce inequality and raise revenue. Firstly, they allow people to internalize the externality by making them pay for the damage they generate, known as the polluter-pay principle. This can act as a deterrent and encourage people to reduce their pollution output. For example, a tax on cigarettes not only raises revenue but also discourages smoking.

Secondly, revenues from pollution taxes can be recycled to achieve less regressive tax reforms. This can be done through transfers and labour income tax cuts, which reduce the tax burden on poorer households. For instance, uniform lump-sum transfers can be provided to all households, or they can be targeted towards those who are more affected by pollution taxes. By ensuring that the most affected households receive sufficient compensation, environmental taxation can promote both efficiency and inequality reduction.

Thirdly, pollution taxes can shift the tax burden from labour to pollution, supporting sustainability objectives. This approach, known as tax shifting or environmental fiscal reform, moves the source of revenue from economic functions like labour to activities that contribute to environmental pollution. For example, carbon taxes aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and can provide the foundation for broad-based tax reforms.

Finally, pollution taxes can raise significant revenues for governments, which can be used to finance public expenditures and redistribute resources. The World Bank reported that in 2022, 37 carbon taxes were implemented or planned, underscoring the growing recognition of their importance. As countries strive for climate neutrality, pollution taxes can play a pivotal role in generating the funds needed for this transition.

In conclusion, taxes on pollution offer a dual advantage of mitigating pollution while also providing fiscal benefits. By carefully considering the distributional impact and recycling the tax revenue, such taxes can effectively reduce inequality and raise much-needed funds for sustainable development.

Cigarettes: Environmental Impact and Pollution

You may want to see also

Taxes levied on suppliers or consumers

The impact of taxes on suppliers or consumers in the context of pollution can be analysed through the lens of microeconomics and the supply-and-demand model. When a tax is levied on suppliers, such as a gas tax, it cuts into their profits. The marginal cost of supplying each unit increases by the amount of the tax, causing the supply curve to shift upwards. This results in a higher price for consumers, who respond by purchasing less. Consequently, the quantity demanded decreases, and the producer surplus is reduced. This dynamic can be observed in the example of a $3 gas tax levied on producers, leading to a new equilibrium with a higher price and lower quantity demanded.

On the other hand, when a tax is levied on consumers, the demand curve shifts downwards. Consumers' willingness to pay decreases, and they adjust their purchasing behaviour accordingly. For instance, if consumers face a $3 tax per gallon of gasoline, they may only purchase a certain quantity if the ticket price is lower. This shift in the demand curve influences the market equilibrium, potentially leading to reduced sales and revenue for producers.

The impact of pollution taxes on suppliers and consumers is also evident in the case of fossil fuel producers, particularly oil producers. A global carbon tax on carbon emissions can significantly affect OPEC and other producers. OPEC, as a cartel, may choose to reduce its production to maintain high prices when the tax is introduced. This decision can result in an almost unchanged crude oil price initially and a shift in the tax burden to consumers during the first 40 years.

To mitigate the regressive impact of carbon taxes on lower-income households, several strategies can be employed. One approach is to direct a certain percentage of the revenue from the carbon tax towards compensating low-income households for their increased energy costs. This ensures that the tax does not disproportionately affect those with lower incomes, who typically spend a larger share of their income on energy. Additionally, a progressive tax system can be implemented, where a tax-free "lifeline" consumption level is granted to each person or household, while higher taxes are applied to more "luxury" levels of consumption.

In summary, taxes levied on suppliers or consumers in response to pollution have significant effects on the market dynamics. They influence the supply and demand curves, prices, quantities demanded, and producer and consumer surpluses. The ultimate impact of these taxes depends on various factors, including the type of tax, the elasticity of demand and supply, and the behavioural responses of consumers and producers.

Understanding Light Pollution Maps: A Beginner's Guide

You may want to see also

How taxes affect the market: shifting the curve

Taxes can be levied in different ways and for different reasons. They can be imposed on income or wealth to raise revenue to finance public expenditure and reduce inequality. Alternatively, they can be imposed on particular goods to raise revenue or to change buying decisions.

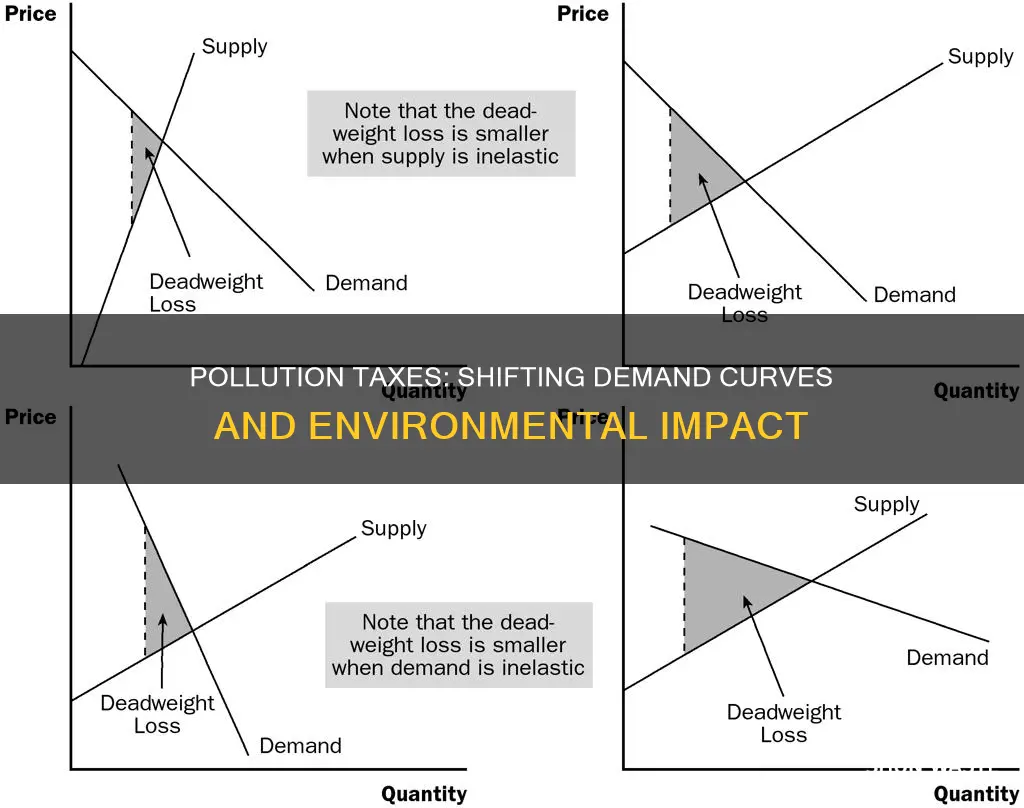

When a tax is levied on a good, the market equilibrium shifts. For example, if a 30% sales tax is imposed on the price of salt, the marginal cost of supplying each unit of salt increases by 30%. This shifts the supply curve: the price is 30% higher at each quantity. The new equilibrium is at a higher price and a lower quantity.

The impact of a tax on the market depends on whether it is levied on the consumer or the producer. This is known as the legal tax incidence. Well-known taxes like the Government Sales Tax (GST) and Provincial Sales Tax (PST) are levied on the consumer. On the other hand, taxes like the gas tax are levied on producers, cutting into their profits. However, the legal incidence of the tax is irrelevant in determining who is impacted by the tax. When a tax is levied on producers, they will pass on some of the costs as increased prices to consumers. Similarly, a tax on consumers will ultimately decrease the quantity demanded and reduce producer surplus.

The wedge method is another way to understand the impact of taxes. This method illustrates that a tax drives a wedge between the price consumers pay and the revenue producers receive, equal to the size of the tax levied. To find the new equilibrium, one needs to find a wedge between the curves equal to the tax amount.

Human Impact: Oceans in Danger

You may want to see also

The wedge method of viewing taxes

The wedge method recognises that the party on whom the tax is levied is irrelevant. Instead, the focus is on the wedge created by the tax. This wedge can be understood as the deviation from the equilibrium price and quantity. As a result of the tax, consumers pay more for the good, and the price received by suppliers decreases. This leads to a new equilibrium, where consumers pay more and producers receive less for the good than they did before the tax.

The wedge method also highlights the market inefficiency that arises from imposing a tax on a good or service. This inefficiency is caused by the higher equilibrium prices paid by consumers and the lower equilibrium quantities sold by producers. The wedge, in this case, represents the amount of deadweight loss created by the tax.

The tax wedge can also be applied to labour markets, where it is used to calculate the percentage of market inefficiency introduced by sales taxes. In this context, the tax wedge is defined as the ratio between the amount of taxes paid by an average single worker and the corresponding total labour cost for the employer. This calculation helps to understand the financial implications of a tax burden imposed on a particular product or service.

Overall, the wedge method of viewing taxes provides a useful framework for analysing the impact of taxes on markets, including the resulting market inefficiencies and the distribution of costs between consumers and producers.

Pollution Rules: Who's in Charge?

You may want to see also

Taxes on pollution as a tool for tackling climate change

Taxation is a powerful tool for achieving policy goals, and carbon taxes are an important mechanism for tackling climate change. By pricing carbon emissions, governments can incentivise the transition to cleaner energy sources and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This approach, known as carbon pricing, aims to incorporate the costs of pollution and climate damage into market prices, encouraging a shift towards less carbon-intensive fuels and the adoption of energy efficiency measures.

Carbon taxes can take various forms, such as direct taxation based on the volume of carbon dioxide emitted or indirect taxation on products or behaviours that contribute to emissions. Well-designed national carbon tax schemes that directly price emissions can serve as essential policy levers for achieving the economy-wide transition to net zero. For instance, Canada has implemented a Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, charging an economy-wide carbon tax that is set to increase gradually from CAD$40 (US$30) in 2019 to CAD$170 (US$128) by 2030. All revenues are returned to the provinces and residents through rebates.

The effectiveness of carbon taxes in reducing emissions is evident. According to estimates, a broad-based tax of around $50 per ton could lead to a decrease in emissions of over 20%. Additionally, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) predicts that global adoption of differentiated carbon prices by 2030 could significantly reduce emissions compared to a baseline scenario. However, it is important to recognise that carbon taxes are not a silver bullet solution, and complementary measures are necessary to address social impacts, spur innovation, and facilitate decarbonisation within the required timeframes.

While carbon taxes can be an effective tool, they also present certain challenges. For instance, reducing emissions through carbon taxes will likely result in lower revenue from taxes paid by highly emissive industries. This potential decrease in tax revenue as petrol and diesel use declines is a significant risk associated with climate change, as recognised in the UK Treasury's 2021 Net Zero Review. To maintain a stable tax base, the review suggested that motorists using electric vehicles should continue to pay taxes to fund public services. Additionally, the government may remove tax relief for green products as they become more prevalent.

In conclusion, taxes on pollution, specifically carbon taxes, are a crucial tool in the fight against climate change. They provide a market-based approach to incentivise the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and promote the adoption of cleaner technologies. However, the successful implementation of carbon taxes requires careful consideration of their impact on tax revenue and the need for complementary measures to address social and economic concerns.

Air Pollutants: The Most Dangerous Killers

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A pollution tax is a tax levied on the emission of pollutants into the environment. It is a form of Pigouvian tax, which is designed to address negative externalities, such as pollution, by incorporating the social cost of these emissions into the market price.

When a tax is levied on pollution, the supply curve shifts upwards by the amount of the tax. This results in a new equilibrium where the price paid by consumers increases and the quantity demanded decreases. The tax revenue collected by the government is equal to the difference between the new consumer price and the producer revenue.

Pollution taxes can lead to a shift in the demand curve. As the price of the good or service increases due to the tax, consumers may become less willing to purchase it, resulting in a downward shift in the demand curve. The magnitude of the shift depends on the elasticity of demand for the good or service.

Yes, there are alternative policy instruments that can be used to address negative externalities such as pollution. For example, the government could implement regulations and standards that directly limit or control the emission of pollutants. Another option is to use market-based instruments such as emissions trading systems, which allow for the buying and selling of pollution permits within a cap on total emissions.